1940-1950

World War II and the Postwar Period

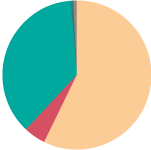

The United States entered World War II in 1942. During the war, immigration decreased. There was fighting in Europe, transportation was interrupted, and the American consulates weren't open. Fewer than 10 percent of the immigration quotas from Europe were used from 1942 to 1945.

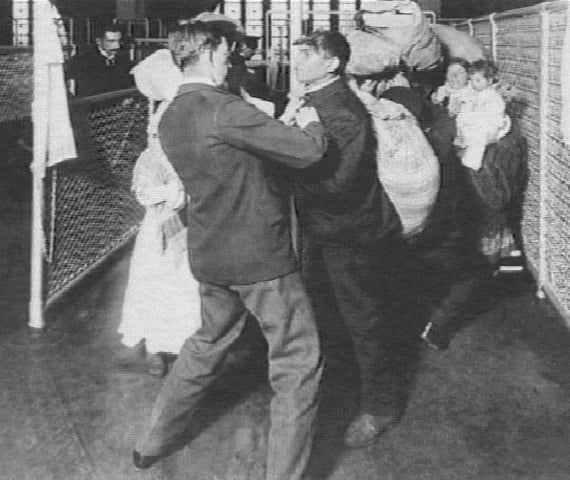

In many ways, the country was still fearful of the influence of foreign-born people. The United States was fighting Germany, Italy, and Japan (also known as the Axis Powers), and the U.S. government decided it would detain certain resident aliens of those countries. (Resident aliens are people who are living permanently in the United States but are not citizens.) Oftentimes, there was no reason for these people to be detained, other than fear and racism.

Beginning in 1942, the government even detained American citizens who were ethnically Japanese. The government did this despite the 14th Amendment of the Constitution, which says "nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty or property without the due process of law."

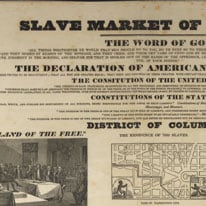

Also because of the war, the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed in 1943. China had quickly become an important ally of the United States against Japan; therefore, the U.S. government did away with the offensive law. Chinese immigrants could once again legally enter the country, although they did so only in small numbers for the next couple of decades.

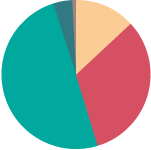

After World War II, the economy began to improve in the United States. Many people wanted to leave war-torn Europe and come to America. President Harry S. Truman urged the government to help the "appalling dislocation" of hundreds of thousands of Europeans. In 1945, Truman said, "everything possible should be done at once to facilitate the entrance of some of these displaced persons and refugees into the United States. "

On January 7, 1948, Truman urged Congress to "pass suitable legislation at once so that this Nation may do its share in caring for homeless and suffering refugees of all faiths.

I believe that the admission of these persons will add to the strength and energy of the Nation."

Congress passed the Displaced Persons Act of 1948. It allowed for refugees to come to the United States who otherwise wouldn't have been allowed to enter under existing immigration law. The Act marked the beginning of a period of refugee immigration.

Learn More