| |

Overview

By Roger Daniels

This child is being evacuated with his parents from Los Angeles, California. Photo Credit: Library of Congress.

This child is being evacuated with his parents from Los Angeles, California. Photo Credit: Library of Congress. |

On December 7, 1941, Japan launched a sneak attack on the American naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. President Franklin D. Roosevelt called it a "date that will live in infamy." America declared war against Japan the next day. Overnight, Japanese Americans found their lives changed. Seventy-four days after Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order No. 9066. The order forced over 110,000 Japanese Americans to leave their homes in California, Washington, and Oregon. They were sent to live in one of ten detention camps in desolate parts of the United States.

None of the Japanese Americans had been charged with a crime against the government. Two-thirds had been born in the United States, and more than 70 percent of the people forced into camps were American citizens.

Roosevelt's action was supported by Congress without a single vote against it, and was eventually upheld as constitutional by the Supreme Court. Yet many scholars came to believe that this order was a "day of infamy" as far as the Constitution and civil rights were concerned. The people forced into camps were deprived of their liberty, a basic freedom of the American Constitution.

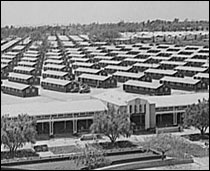

The barracks at the Santa Anita reception center, Los Angeles County, California. Photo Credit: Library of Congress.

The barracks at the Santa Anita reception center, Los Angeles County, California. Photo Credit: Library of Congress. |

The government called these camps "relocation

centers." Surrounded by barbed wire and guarded by armed soldiers,

families lived in poorly built, overcrowded barracks

. The barracks themselves had no running water and little heat. There

was almost no privacy, and everyone had to use public bathrooms.

The camps provided medical care and schools for the Japanese Americans. As time went by, more and more individuals, mostly young adults, were released to do farm and defense work, go to college, and even serve in the military.

Almost 50 years later, the American Congress passed and President Ronald W. Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which formally apologized for its wartime imprisonment of these innocent people and awarded each of 80,000 survivors a $20,000 payment.

Why were Japanese Americans moved out of their homes and into camps, especially when German and Italian Americans were not? There have been numerous explanations. Perhaps the best explanation was given by the Presidential Commission that recommended the 1988 apology. The commission said that the "broad historical causes were … race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership. Widespread ignorance of Japanese Americans contributed to a policy conceived in haste and executed in an atmosphere of fear and anger at Japan."

It is important to remember that this was before the civil rights movement. Racism against people of color - Asians, Latins, and African Americans - was common. Because they were easily identifiable as being Asian, Japanese Americans felt more racial hatred than German Americans and Italian Americans.

Roger Daniels, professor of History at the University of Cincinnati, is the author of Prisoners Without Trial: Japanese Americans in World War II.

Roger Daniels, professor of History at the University of Cincinnati, is the author of Prisoners Without Trial: Japanese Americans in World War II. |

In addition, Japan put together an impressive string of victories in the first six months of the war, overwhelming U.S. troops in the Philippines, sinking many U.S. ships, and conquering much of Southeast Asia. Their victories led to U.S. paranoia, and many people thought their Japanese neighbors could be spies. These victories, combined with racism, created a war hysteria. People were afraid, and they thought that the only way that America could be safe was to put the Japanese Americans in camps.

This fear continued through most of World War II. Even when it was clear that Japan was losing the war, most of the Japanese Americans were kept in camps well into 1944. The last camp did not close until March 1946, seven months after the war had ended.

Norman Mineta's story is just one boy's experience of living in an internment camp. Every Japanese American from this time in history has his or her own story to tell. This is Norman's.

|

|